DNA Test

| Category | POSITIVE | CARRIER | CLEAR |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ophthalmologic - Associated with the eyes and associated structures |

2 |

- |

- |

|

Urinary system / Urologic - Associated with the kidneys, bladder, ureters and urethra |

- |

1 |

- |

|

Immunologic - Associated with the organs and cells of the immune system |

- |

- |

- |

|

Metabolic - Associated with the enzymes and metabolic processes of cells |

- |

- |

- |

|

Musculoskeletal - Associated with muscles, bones and associated structures |

- |

- |

- |

|

Nervous system / Neurologic - Associated with the brain, spinal cord and nerves |

2 |

- |

- |

Endocrine - Associated with hormone-producing organs |

- |

- |

- |

|

Cardiovascular - Associated with the heart and blood vessels |

- |

- |

- |

|

Haemolymphatic - Associated with the blood and lymph |

- |

- |

- |

|

Digestive system / Gastrointestinal - Associated with the organs and structures of the digestive system |

- |

- |

- |

|

Dermatologic - Associated with the skin |

- |

- |

- |

|

Reproductive - Associated with the reproductive tract |

- |

- |

- |

|

Respiratory - Associated with the lungs and respiratory system |

- |

- |

- |

|

Trait (Associated with Phenotype) |

- |

- |

- |

Confirmed medical conditions:

Current medications:

My Clinic:

This Breed of does not have any documented genetic predisposition to a specific disease at the current time. This does not necessarily mean that this breed does not have any genes predisposing to a certain disease, but instead this may be due to the fact that it is a relatively new or rare breed, and/or there has been insufficient collection of data to document such predisposition to date. We continue to monitor all breeds for the emergence of patterns of disease occurrence, and it is always a good idea to speak to your veterinarian and/or breeder regarding any disease that may occur in your pet. Remember, just because a disease may be more common in certain breeds, does not mean your pet will go on to develop this disease - we are referring to average likelihoods only.

Below we have outlined some of the most common diseases that occur in more generally

| Disease | Estimated Prevalance | Result |

|---|---|---|

|

Allergy and Atopy |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

Note: there is no routine screening available prior to development of clinical signs.

Overview

Allergic and immune mediated diseases are becoming much more prevalent in dogs in the last 1-2 decades. Allergic diseases are thought likely have a genetic predisposition, but environmental triggers play a major role in their development.

Allergic dermatitis is a very common skin problem in dogs, and can be due to things such as flea allergy, food allergy and allergy to plants or other substances in the environment (e.g. moulds, dust mites, pollens). The latter type of allergic dermatitis is called atopy. Differentiating food allergy from atopy can be a major diagnostic challenge, involving food trials that may take months to complete. It is also possible for both conditions to be present in the one animal at the same time.

Atopy is a very common condition which has also been referred to as allergic inhalant dermatitis. Affected dogs develop an allergic reaction to common environmental substances, such as pollens, moulds and house dust, which are inhaled in the normal course of the dog’s life. Atopy is strongly heritable, and affected dogs are thought to inherit a genetic predisposition to develop allergic antibodies. Diagnosis is by skin testing with allergens (allergy skin test), which is much more accurate than blood tests, and is performed by veterinary dermatologists.

Affected dogs have generalised itchiness, and will scratch, lick or chew at their feet and other areas of their skin. They can sometimes damage their skin quite severely, and secondary bacterial infection once the skin is damaged is quite common. Sneezing and other respiratory signs are not common, despite the allergen being inhaled - only around 15% of affected dogs show respiratory signs (except in the Dalmatian, which is much more likely to sneeze).

Treatment can involve various anti-inflammatory and immune-suppressing drugs, as well as desensitisation therapy, fatty acid supplements and various lotions and shampoos. Secondary infections are also treated as they arise. Immunotherapy (allergen specific desensitisation) is the best option available to control the condition in the long term, without the side effects of steroids and other immune-suppressing drugs. |

||

|

Cranial Cruciate Ligament Rupture |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

There is no screening test available for this condition prior to actual ligament rupture.

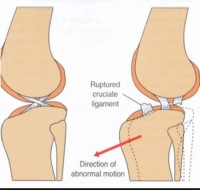

Overview

Cranial cruciate ligament rupture is a common injury in dogs, with a prevalence of 2.55% reported across the dog population in general. Any breed and any dog can be affected by this condition. Some breeds are predisposed to this condition however, with the prevalence in the Rottweiler reported to be 8.3%. It is believed that this condition occurs more in these breeds not just due to trauma, but due to degeneration of the ligament itself leading to a weakness of the ligament. Factors that contribute to ligament degeneration include: obesity, osteoarthritis and other inflammatory joint conditions, as well as genetics.

Cranial cruciate ligament rupture causes acute lameness in the affected hind limb. The torn ligament and resulting instability of the stifle (knee) joint leads to inflammation, and eventually joint capsule thickening in an attempt to stabilise the joint. Arthritic changes will also develop over time. The most common age that this injury occurs in dogs is 7 – 10 years, with large breeds tending to be affected at a younger age than smaller breeds. Diagnosis is indicated by a positive drawer sign on examination on the joint, and definitively by x-rays with a specific “picture” of the knee required (stressed view with tibial compression). Often sedation or anaesthesia is required for a full examination due to the pain in the joint. Surgical repair is usually required to stabilise the joint and reduce the risk of arthritis later in life. It is not uncommon for the opposite cruciate to also rupture at some time in the future. In some dogs, especially small dogs, medical management can be successful. However, because the knee joint is unstable, it is always prone to injury more easily in the future, and once arthritis forms (which is the body’s attempt to stabilise the area) surgery will no longer take away your dog’s pain. The decision to go ahead with surgical repair of the joint is best made early for best results to be obtained. You should also spend some time researching the experience level and results previously obtained by your surgeon, and do not be afraid to seek a second opinion! Surgery is generally always recommended in large dogs, and several techniques are available. |

||

|

Cutaneous Asthenia (Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome). |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. There is currently no screening to detect carriers of this disease - it will be readily apparent in affected animals from a young age.

Overview

This is a group of collagen disorders that mainly affect the skin, resulting in skin with the tensile strength that is only 1/27th that of normal skin. There are a number of different genetic mutations that can cause one of these collagen defects. Research suggests that most of these defects in collagen in dogs are transmitted as dominant traits, while some others are recessively inherited (as occurs in people). The result is a puppy with skin that tears very easily with only minor trauma (such as scratching) and tends to heal with large scars. The skin often hangs in loose folds, and will stretch excessively. Skin tears will heal normally if sutured, but can become larger if left untreated.

Diagnosis can be made by performing a skin extensibility test, and skin biopsies can help confirm the diagnosis. There is no treatment, and management aims to reduce the risk of injury to the affected animal (e.g. padding sharp corners around the house, avoiding rough play or running where injury may occur, providing soft padded bedding etc).

Sometimes other abnormalities may be present as well, such as developmental eye abnormalities, cataracts, loose joints, lumps under the skin and easily bruised skin due to fragile blood vessels. There is no cure for Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. |

||

|

Elbow Dysplasia |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Recognized radiographic screening technique under general anaesthesia at 12 - 24 months of age (usually done at same time as hip dysplasia screening) and assessed by accredited radiologist.

Overview

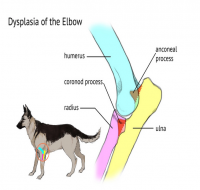

Elbow dysplasia refers to a group of four developmental disorders affecting the elbow and leading to forelimb lameness in large breed dogs. It is inherited, and has a high heritability, with certain breeds showing increased prevalence of the disease.

One or more of the following abnormalities may be seen in either one or both elbows of affected animals: Ununited anconeal process (UAP) Fragmented medial coronoid process (FCP) Osteochondrosis of the medial humeral condyle (osteochondritis dissecans, or OCD, occurs once a cartilage flap forms in the joint) Incongruity due to asynchronous proximal growth of the radius and ulna

Elbow dysplasia is one of the most common causes of forelimb lameness in large breed dogs. Onset of joint pain is usually between 4 – 10 months, with lameness made worse following exercise. Some dogs may not show pain and lameness until later in life, when degenerative joint changes and arthritis becomes apparent.

Treatment depends on the type of abnormality that is present, which is determined by x-ray. FCP is the most common form of elbow dysplasia in dogs, and for this form of the disease medical management is usually recommended, as surgical treatment has not been shown to improve the outcome for the patient. Other forms of elbow dysplasia regularly seen, OCD of the elbow and UAP, are recommended to be treated surgically to obtain the best outcome, and the prognosis is good if surgery is performed as early as possible, before any bony joint change (e.g. arthritis) occurs. |

||

|

Epilepsy (Idiopathic, Primary or Inherited Seizures) |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

No screening currently available - thorough work up of all cases of seizure recommended.

Overview

Epilepsy is a disease characterised by seizures, and is diagnosed by ruling out all possible reasons or causes for seizures – causes such as disease or trauma to the brain, metabolic disease (such as low levels of glucose or calcium in the blood), or exposure to toxins. When no cause for seizures is present, this is called primary or idiopathic seizures - or epilepsy - and is generally accepted to have a genetic basis. The precise method of inheritance is not known, but is suspected to be recessive and affected by several genes.

Epilepsy generally presents between 1.5 and 3 years of age, although it may be seen between 6 months and 5 years. Dogs whose seizures begin at less than 2 years of age are more likely to have severe disease that is more difficult to control.

Seizures are almost always generalised, or “grand mal” type, and will begin initially as a single seizure followed by recovery. Also called “tonic-clonic” seizures, there is a period where the dog goes stiff and falls (if standing), followed by a variable period of repeated muscle contractions (jaw chomping, legs jerking). Salivation occurs and loss of bladder and/or bowel control may also occur. The seizure will last up to a minute or two, followed by a variable recovery period.

Epilepsy cannot be cured, and a dog will continue to suffer seizures for the rest of its life. Seizures tend to occur more and more frequently if the condition is left untreated, and can be fatal in severe cases. Treatment is with anti-seizure medication (anticonvulsants), and aims to reduce the occurrence and severity of seizures. |

||

|

Histiocytic Sarcoma Complex |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

None available at this time.

Overview

Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) complex comprises several diseases, including histiocytic sarcoma and malignant histiocytosis (MH). The names of these diseases are taken from the Histiocyte Society, an expert group in the field of histiocytic diseases.

Localised histiocytic sarcoma may be seen on the lower limbs, or around the joints. It is a cancer of histiocytic cells, which are specialised immune cells that are involved in collecting and presenting antigen to white blood cells. If a localised HS is treated early enough, it may have a good prognosis. Surgical removal of the mass is required, and if a joint is involved limb amputation may be required. It is important that all cancerous cells are removed to avoid recurrence and spread to other organs.

Disseminated histiocytic sarcoma is when an initial HS has undergone extensive spread throughout the body. It generally arises from a tumour in a hidden site, such as the lung or spleen. This type of HS is very difficult to treat, as there is cancerous disease in multiple tissues. Malignant histiocytosis is similar to disseminated HS in that MH is an aggressive disease where the cancer arises in multiple tissues at once. MH is thought to be rare, although it is difficult to differentiate from disseminated HS clinically.

The HS complex of diseases is most commonly recognised in the Bernese mountain dog, although it is seen in several other breeds, including the golden retriever, flat-coated retriever and Rottweiler. In the Berner there is a familial pattern of inheritance, although the exact genetic mechanism of inheritance has yet to be determined. Common signs of HS include lethargy, weight loss and loss of appetite. If the lymph nodes of the lungs are involved there may be a cough or difficult respiration. Sometimes tumours in the spine occur, leading to hind limb paralysis, or cancer in the brain may lead to seizures.

The treatment for disseminated HS and MH is chemotherapy, however the response to such treatment to date has generally been brief. The prognosis is poor for both forms of disease, and both will ultimately lead to death or euthanasia. |

||

|

Hypothyroidism |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Consider TgAA at 2, 3, 4 & 6 years (generally used in pure breed breeding certification programs).

1. Thyroid panel - ie baseline Total T4 & TSH. (Run tests in a “well” dog) - recommend annually from two years of age.

Overview

Hypothyroidism is the most common endocrine (hormonal) disease in dogs, and most commonly occurs due to an immune-mediated process where the immune system destroys the thyroid gland (called lymphocytic thyroiditis). It is thought that the end stage of this immune-mediated destruction is an atrophied, fatty thyroid gland.

Hypothyroidism is a complex and progressive disease that is often not diagnosed until signs are well progressed, as early signs are non-specific and can vary widely. They may consist (in the younger adult dog) of vague signs such as reduced energy levels, or increased susceptibility to infections. Most veterinarians and owners do not test for this disease every time a relatively young dog gets an infection! Also, when an animal is unwell, their thyroid hormone level is likely to be low regardless of how healthy their thyroid gland is, (called "sick euthyroid syndrome") which further complicates attempts to get an early diagnosis.

Late stage (advanced) signs of disease such as bilateral symmetrical alopecia (hair loss on both sides of the body), weight gain, poor cold tolerance and failure of clipped hair to regrow are more recognisable to the owner and veterinarian as signs of serious illness, although these signs are generally not seen until middle age or later. These signs will generally lead a veterinarian to test for hypothyroidism.

In almost all breeds there is currently no DNA test for hypothyroidism, however there are recent improvements in screening tests, and in countries such as the UK and USA there are breeding certification programs for hypothyroidism (e.g.; Orthopedic Foundation for Animals Hypothyroidism Certification Program - see http://www.offa.org)

The OFA program bases certification on the thyroid hormone level test (fT4 and TSH), as well as a test for antibodies against thyroglobulin (TgAA), which is a good indicator for lymphocytic thyroiditis. Testing as young as 1 year of age can pick up this disease, and certification for breeding can be provided, although re-testing at 2, 3, 4 and 6 years is recommended for dogs testing normal at 12 months. It is strongly recommended that affected dogs not be used for breeding.

Treatment of hypothyroidism is with daily hormone replacement using a synthetic thyroid hormone. This aims to maintain approximately normal levels of thyroid hormone within the animal. Lifelong treatment is required, and if maintained, dogs will generally lead a normal, healthy life. |

||

|

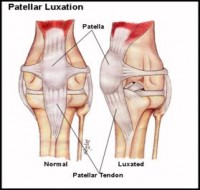

Luxating patella |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Easily detected on examination and manipulation by experienced veterinarian - should check for this in puppies if is a predisposed breed.

Overview

Luxating patella refers to a kneecap that can dislocate in and out of the groove that it normally sits in. Medial luxation (dislocation inwards, or towards the other leg) is considered heritable, and is usually seen in relatively young dogs and in small and toy breeds. Lateral luxation (dislocation outwards, away from the other leg) is seen later in life, around the age of 5 – 8 years in toy breeds, and heritability has not been proven as yet. In contrast, lateral luxation in large breeds is seen at around 5 – 6 months of age.

Luxating patella is a congenital problem (it is due to the conformation of the knee, and is present from birth), but the degree to which the patella can move out of the patellar groove of the knee tends to increase over time. The degree of luxation (dislocation) can be graded on a scale of 1 – 4, based on clinical examination by the veterinarian and on the amount of change to the knee joint (stifle) on x-ray.

Clinical signs of luxating patella may be hard to detect initially. Dogs may “skip” a step when running, or “bunny hop” in the back legs. Untreated, luxating patella will wear away at the bone of the leg on each side of the patellar groove, and arthritis will develop. This can lead to severe pain and lameness as a dog gets older.

In young dogs, surgery is generally recommended to correct the problem before bony changes and arthritis sets in. However surgery is less likely to be helpful once arthritis is present, and in older dogs’ treatment is generally aimed at managing pain. |

||

|

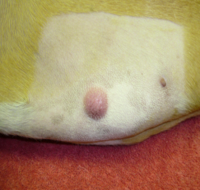

Mast Cell Tumour |

No prevalence data is currently available

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

Thorough examination and palpation of skin surface (cutaneous form) annually at each veterinary check-up.

Overview

Mast cells are a type of immune cell involved in allergy and inflammation that is found in many tissues in the body. Mast cell tumours of the skin (also called mastocytoma) are the most common skin cancer of dogs, and are thought to account for between 15 - 20% of canine skin tumours. Mast cell tumours may also be found throughout the body, commonly in organs such as the intestine, spleen or liver. Certain breeds with a predisposition for mast cell tumours include brachycephalic breeds (e.g. boxers, Boston terriers, bulldogs, pugs), retriever breeds and Rhodesian ridgebacks.

Mast cell tumours are commonly malignant, and are graded as to their severity by a specialist pathologist. This helps to determine the treatment protocol and likely prognosis. The outlook for a grade I mast cell tumour of the skin is relatively good, while a grade III-IV mast cell tumour carries a poor outlook, as the likelihood of prior spread (metastasis) is high. Mast cell tumours are locally invasive, and generally require surgical removal with as wide a margin as possible to ensure no tumour cells are left behind.

Mast cell tumours of the skin can be variable in appearance, and may appear quite suddenly and grow quickly, or may not change much at all for months, followed by sudden rapid growth. Multiple lumps may appear at the same time. Lumps may be raised and discrete, soft or solid feeling, or with more diffuse borders. Release of inflammatory mediators such as histamine from tumours may lead to local and systemic signs, with the most common reported to be gastric ulceration (in around 25% of dogs).

Diagnosis of mast cell tumour is generally by aspiration or biopsy of a tumour and examination by a veterinary pathologist. As well as surgery, treatment may also include chemotherapy, radiation therapy and supportive medical therapy with H1 and H2 histamine blockers, antacids (e.g. proton pump inhibitors), sucralfate and occasionally misoprostol. The prognosis is largely dependent on the staging of the tumour/s. |

||

|

Subaortic Stenosis |

|

|

|

Screening Suggestions

1. Auscultation at each puppy veterinary examination.

2. Echocardiography in any puppy with a persistent cardiac murmur (present at 2nd and/or 3rd puppy visit) Overview

This is a congenital heart defect involving a narrowing just below the aortic valve. The aortic valve lies between the left ventricle and the aorta, the main artery leading out of the heart to the body. The narrowing of the subaortic stenosis (SAS) results in restriction to normal blood flow and high-pressure flow across the valve, causing the heart to have to work harder when it contracts. This commonly results in abnormalities in the heart muscle, and abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias).

This condition is often seen in larger breeds, and in most breeds is suspected to have a dominant mode of inheritance with variable penetrance. The specific genetic model has not been determined in the Rottweiler as yet, and in the golden retriever it is thought that it may be transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait. Turbulent high pressure flow across the aortic valve results in a murmur. Other signs are usually seen between 6 – 18 months of age, and may include cough, fainting, exercise intolerance and lethargy. Some dogs may just experience sudden death due to arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms).

The condition is diagnosed by echocardiography (a heart ultrasound) performed by a veterinary cardiologist in a puppy with a persistent cardiac murmur. Treatment is difficult, and affected dogs often die between 1 – 3 years of age either due to heart failure or sudden death (due to arrhythmia). |

||

These conditions are reported to have a breed predilection in the Mixed Breed, although they are less common than those mentioned earlier, or have less of an impact on the animal when they occur. Hence they are not covered in detail in this article, however further information can be found by clicking on any diseases that are highlited. This list is not a comprehensive list of all diseases Unknown may be prone to.